Birds of the forests

Forests offer food and shelter some of the richest and most diverse variety of birds.

Birds of the forest employ different survival strategies. Some change their mating habits depending on the availability of food. Others endure long migrations south for the winter. Some forest birds have developed complex, language-like calls.

Two forest-dwelling birds that were quite common in Audubon’s day, the Carolina Parrot (Carolina Parakeet) and the Passenger Pigeon, were hunted to extinction by the early 20th century.

“The air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse…“

—John James Audubon describing the Passenger Pigeon in his Ornithological Biography.

The Passenger Pigeon, once the most abundant bird of North America, was hunted to extinction by the early 20th century.

In Audubon’s time, they travelled in massive flocks that could blot out the sky like an eclipse.

The pigeons were hunted mercilessly, and their tendency to fly in dense flocks made them easy prey.

In his writings, Audubon vividly describes a scene where a group of hunters used poles to knock down thousands of pigeons as the flocks flew overhead.

“The stacks of grain put up in the field are resorted to by flocks of these birds, which frequently over them so entirely, that they present to the eye the same effect as if a brilliantly coloured carpet had been thrown over them.”

—John James Audubon describing the Carolina Parrot in his Ornithological Biography.

Like the passenger pigeon, the Carolina Parakeet was once abundant. It was slaughtered in large numbers because it was considered a pest.

Described by Audubon as “always an unwelcome visitor to the planter, the farmer, or the gardener”, the parakeet had an unfortunate habit of swarming a grain field and destroying “twice as much of the grain as would suffice to satisfy [its] hunger”.

By the 1920s, the Carolina parakeet was declared extinct.

This tiny songbird migrates to South America every winter — a non-stop flight of up to 88 hours.

To prepare for such a taxing effort, the Warbler gorges on food and nearly doubles its weight before the flight.

North America’s largest owl, its great size is made up almost entirely of thick fluffy feathers.

The Great Gray Owl is a reclusive bird, living in deep forests away from human activity.

Unaware of the potential danger that humans pose, the owl is tame and easily approached. Hunters have described occasions where they were able to catch the bird by hand.

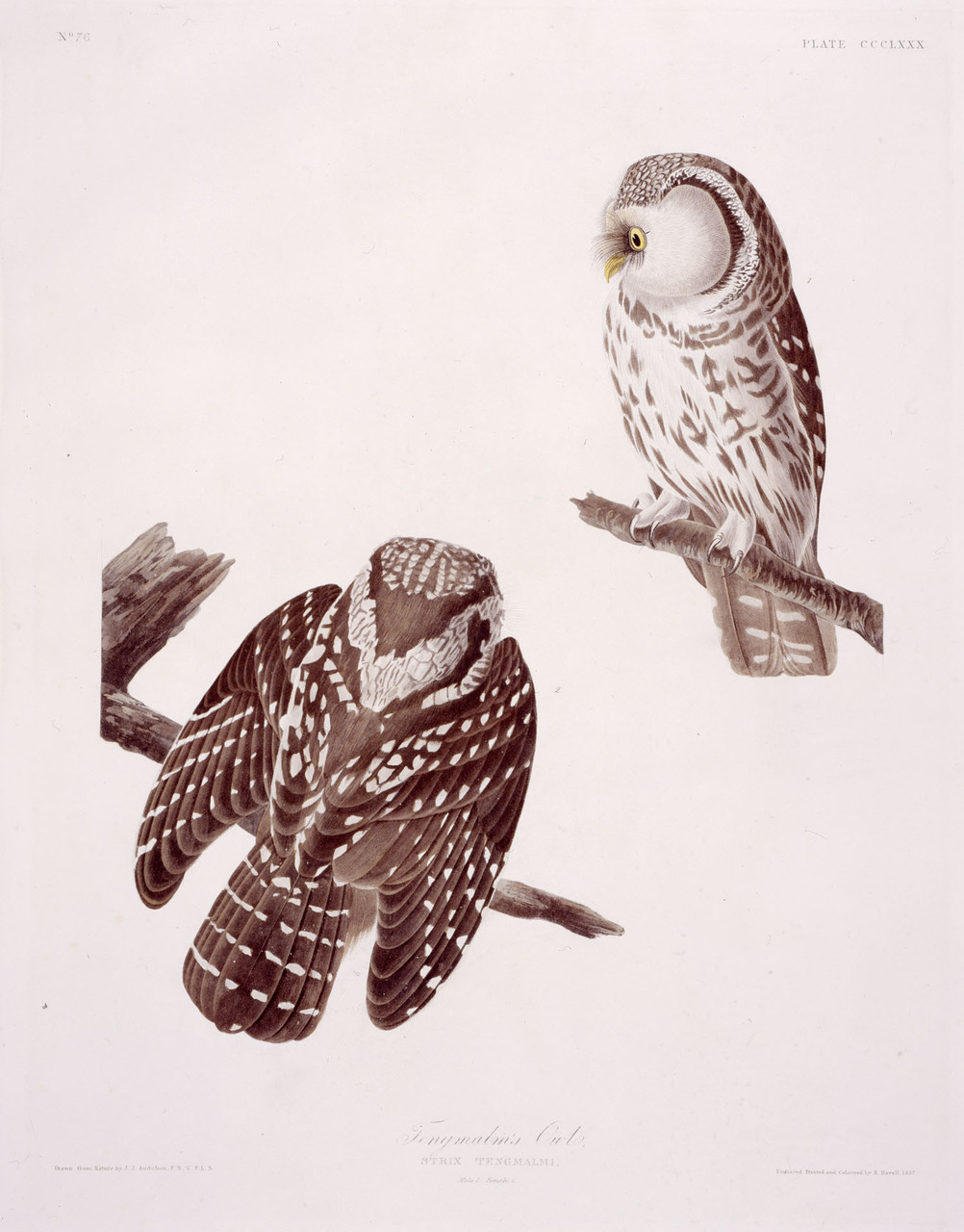

A nocturnal hunter, the Boreal Owl can be dazzled by light if it accidentally wanders out during the day, making it vulnerable to being caught by hand.

Audubon depicted the owl with minimal details of its habitat as he never saw the bird alive in the wild.

Chesnut-backed Titmouse, Black-capt Titmouse, Chesnut-crowned Titmouse (Plate 353)

Chesnut-backed chickadee, Black-capped chickadee, and Bushtit

Parus rufescens, Parus atricapillus, and Psaltriparus minimus

1837

In his rush to complete The Birds of America, Audubon would often fit multiple small bird species onto a single sheet. In this scene, four chickadees gather around the long hanging nest of the bushtits, the pair on the right.

The language-like calls of the chickadees are complex and communicate a wide range of information, from the location of other flocks to the presence of predators.

Birds that associate with chickadee flocks, such as bushtits, understand chickadee’s alarm calls even though they don’t speak the same “language”.

“They usually hunt in pairs during the whole year; and although they build a new nest every spring, they are fond of resorting to the same parts of the woods for that purpose. I knew the pair represented in the plate for three years, and saw their nest each spring placed within a few hundred yards of the spot in which that of the preceding year was.”

—John James Audubon describing the Red-shouldered Hawk in his Ornithological Biography.

“This bird, when surprised, is subject to very singular and astonishing fits of terror. While in Louisiana, I have several times crept up to one occupied in searching for food […] I have taken my cap and suddenly struck the stump, as if with the intention of securing the bird; on which the latter instantly seemed to lose all power or presence of mind, and fell to the ground as if dead."

—John James Audubon describing the Pileated Woodpecker in his Ornithological Biography.

“The borders of murmuring streamlets, overshadowed by the dense foliage of the lofty trees growing on the gentle declivities, amidst which the sunbeams seldom penetrate, are its favourite resorts. There it is, kind reader, that the musical powers of this hermit of the woods must be heard, to be fully appreciated and enjoyed.”

—John James Audubon describing the Wood Thrush in his Ornithological Biography.