Birds of the wetlands

One of the richest and nost diverse ecosystems, wetlands support many species of birds. Wetlands provide abundant food, cover and nesting ground, as well as resting ground for migratory birds. Marshes, bogs and swamps are all different types of wetlands.

Wetlands have disappeared at an astonishing rate since Audubon’s time. Birds have been especially affected by this loss. The Bachman’s Warbler is now on the verge of extinction – a victim of a habitat loss.

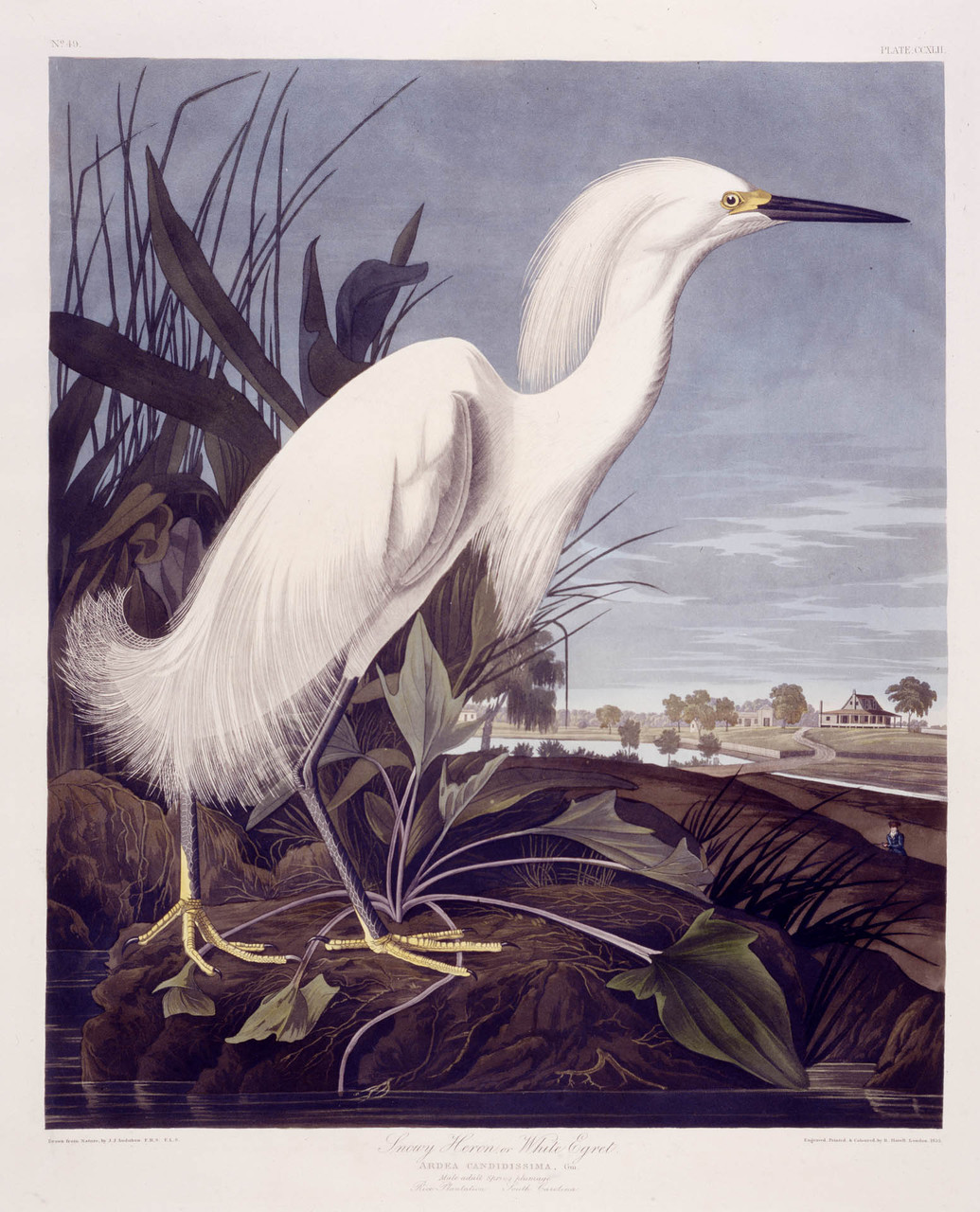

There are also success stories: both the Whooping Crane and White Egret (Snowy Heron) have been brought back from the brink of extinction thanks to ongoing conservation efforts.

This shy and reclusive warbler may be lost forever. The Bachman’s Warbler has not been seen since 1988.

Already rare in Audubon’s time, Audubon never saw the species in the wild. He drew the bird from specimens belonging to his friend Reverend John Bachman and named the bird in his honour.

The Snowy Heron, also called the White Egret, was hunted for its long, wispy feathers which were in high demand as decoration for women’s hats.

By the early 1900s, the egret had nearly vanished. Early conservationists stepped in and ensured the species’ successful recovery.

The figure of a hunter depicted in the background is thought to be a self-portrait of Audubon.

“Proud of its beautiful form, and prouder still of its power of flight, it stalks over the withering grasses with all the majesty of a gallant chief.”

—John James Audubon describing the Whooping Crane in his Ornithological Biography.

The tallest bird in North America, the Whooping Crane is a success story of conservation and recovery.

In the 1940s, only about 15 birds remained. Today, there are about 600 of them.

Audubon had to depict his subject in an awkward pose in order to fit the entire life-sized crane on the page, already the largest paper available for printing at the time.

“The congregated Redwings fall upon the fields in such astonishing numbers as to seem capable of completely veiling them under the shade of their wings.”

—John James Audubon describing the Red-winged Starling in his Ornithological Biography.

Red-winged Blackbirds are considered to be one of the most abundant land birds on the continent.

They fearlessly defend their territories and chase off birds much larger than themselves, such as crows.

Audubon rendered the bird in four different poses to capture its various markings.

This noisy inhabitant of marshes sings throughout the day and all night.

The Marsh Wren is a common sight. With an increasing population and a vast range, this species is listed as being of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

“Look on the one that stands near the margin of the pure stream: see his reflection dipping as it were into the smooth water, the bottom of which it might reach had it not to contend with the numerous boughs of those magnificent trees. How calm, how silent, how grand is the scene!”

—John James Audubon describing the Great Blue Heron in his Ornithological Biography.

“Through the dim light your eye catches a glimpse of the white-plumaged birds, moving rapidly like spectres to and fro. The loud cracking of their mandibles apprises you of the havoc they commit among the terrified inhabitants of the waters.”

—John James Audubon describing the Wood Ibis in his Ornithological Biography.

“Up the creek the Mergansers proceed, washing their bodies by short plunges, and splashing up the water about them. Then they plume themselves, and anoint their feathers, now and then emitting a low grunting note of pleasure.”

—John James Audubon describing the Hooded Merganser in his Ornithological Biography.