Freedom-seekers

When John Graves Simcoe passed An Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude in 1793, he set the newly founded colony of Upper Canada on a steady path toward freedom. Although the Act did not abolish slavery, it limited the reach of slavery as an institution, and set the tone for the development of civil rights in what would one day become Ontario.

The dream of freedom lured black Americans, enslaved and free, northward. American soldiers fought "black men in red coats" on the borders of Upper Canada in the War of 1812. Returning home with the news in the company of their own enslaved servants, soon African-American men, women and children across the South realized that liberty might be attained in Upper Canada.

Most freedom-seekers settled in communities close to the American border. Others found new homes in the Town of York. Early York provided opportunity: there was a need for skilled tradesmen in the growing town, and the first black settlers found work building roads, farming and selling produce to local markets. They worked in construction, in personal service, in dressmaking and in millinery. They were carpenters, coachmen, draymen and hostlers. The Town of York was a place to build a home and a future.

By 1834, slavery had been abolished thoughout the British colonies. Toronto was a burgeoning city where schools, churches and public institutions were open to every immigrant, black or white. Early Toronto was a centre of political and economic growth, where Emancipation Day was celebrated with parades and banquets every August 1, and where protests against American slavery would continue through to the end of the Civil War.

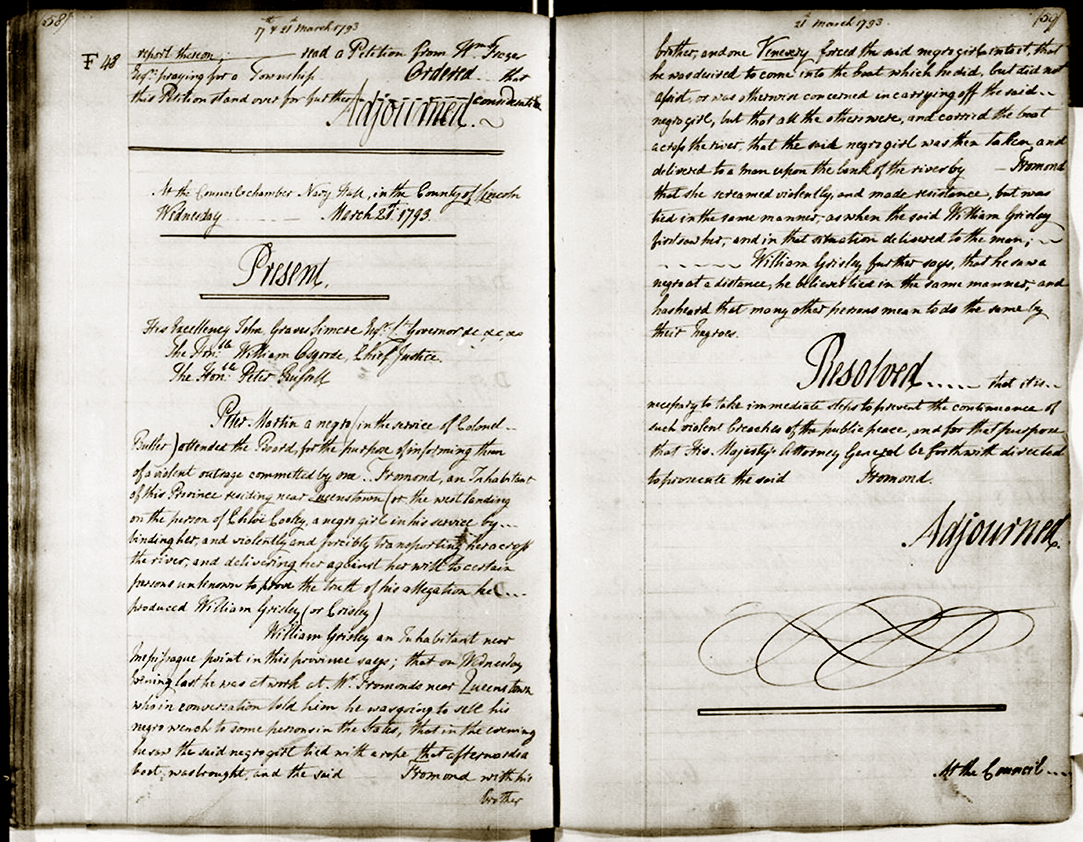

Land & State book, Upper Canada, Volume A 8th July 1792-27th June 1796, pp. 58-59, entry for March 21, 1793

Courtesy of Library & Archives Canada

In 1793, Chloe Cooley, an enslaved girl from Queenston was bound, gagged and forced into a small boat to be sold across the Niagara River into the United States by her owner, Adam Vrooman. It was a violent and shocking incident: her struggle and defiance were witnessed by Peter Martin, a Black Loyalist, and William Grisely, a white Loyalist veteran. They brought the case to the attention of Lieutenant Governor Simcoe. Simcoe had tried to abolish slavery in his first Parliament in Upper Canada, but had been blocked by slaveholders on his Executive Council. The Chloe Cooley Incident gave Simcoe the political capital he needed to pass the first gradual abolition law in the British Empire.

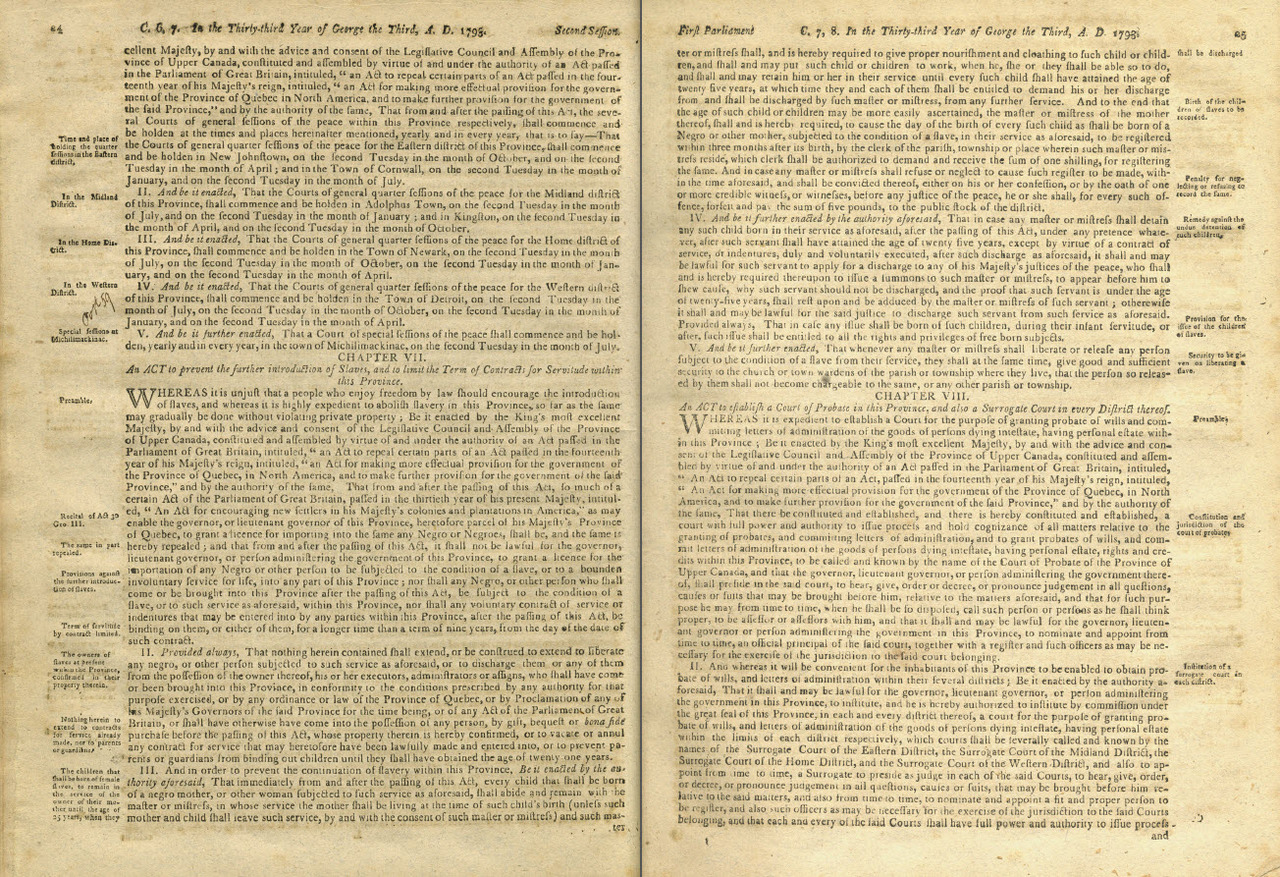

Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude

June 19, 1793

From The statutes of His Majesty’s province of Upper Canada, in North-America

Town of York: Printed by John Cameron, 1793-1841

Three months after the Chloe Cooley incident, Lieutenant Governor Simcoe passed the Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude. The bill limited, but did not abolish slavery. It stated that slaves who entered the province would be considered legally free and that the importation of slaves would cease. Although those already living in the colony remained the property of their owners, their enslaved children would be freed at the age of 25, and their children would be born into freedom. It would be forty years before slavery would be abolished in the rest of the British Empire.

John Graves Simcoe was a military officer who had fought alongside Black Loyalists during the American Revolution. Following his military career, he entered Parliament and supported William Wilberforce’s attempts to end Britain’s involvement in the African slave trade. When he was named the first Lieutenant Governor of the newly founded colony of Upper Canada, he became the first British colonial administrator to pass antislavery legislation.

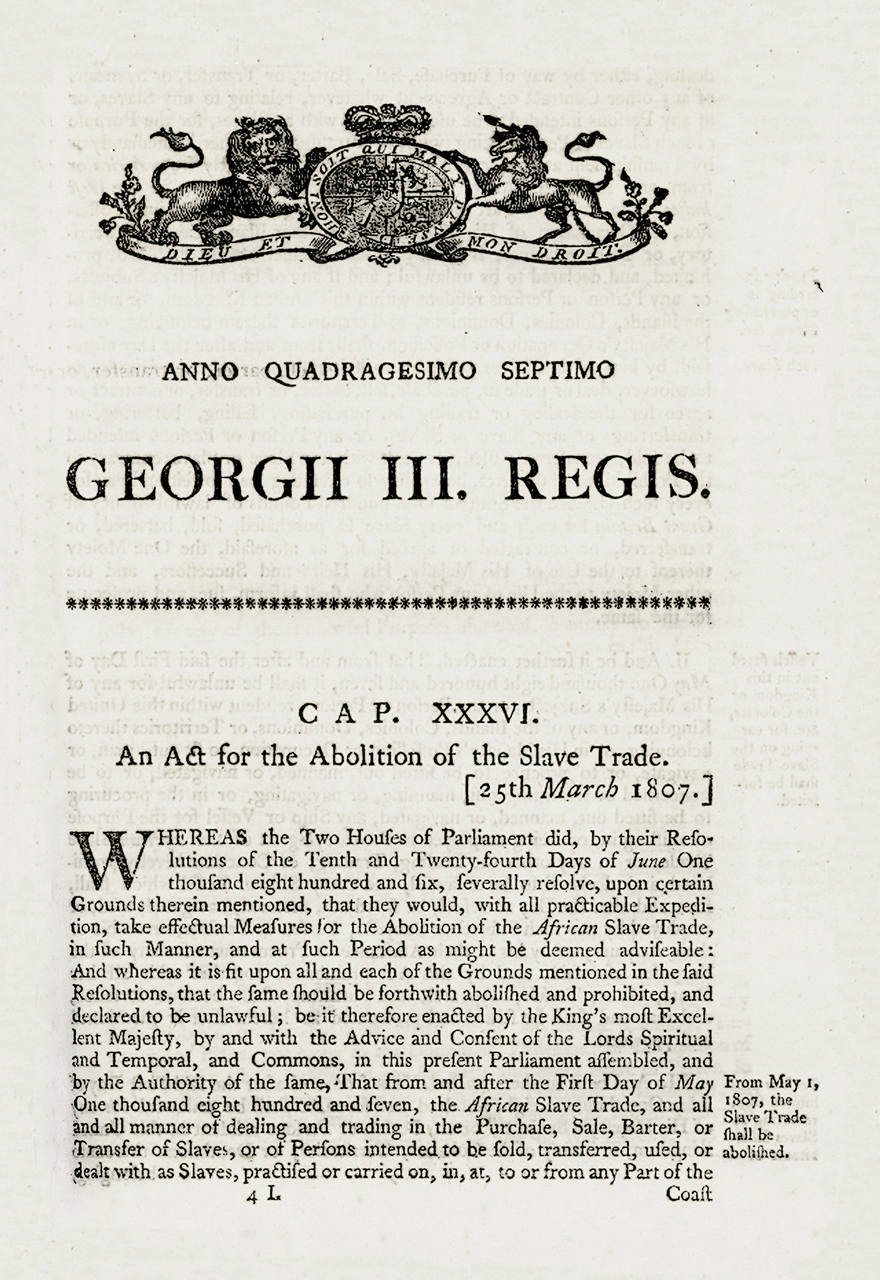

Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, 1807

C.33 in the 47th year of George III. AD. 1790. Cap XXXVI

This landmark piece of legislation, passed by the British government in 1807, made the transportation of slaves in British-owned ships illegal. While this effectively ended Great Britain’s part in the transatlantic slave trade, it was still legal to own slaves in the Town of York, as it was in the rest of the British Empire. It wasn't until the Emancipation Act of 1833, which came into effect on August 1, 1834, that slavery was abolished throughout the British colonies.

This view looking east along Front Street East from Jarvis Street is after a painting by Surgeon Edwin Walsh of the 49th Regiment of the British Army stationed in York. In 1803, there were approximately 375 people living in the Town of York. This early view shows the homes of some of the elite families of York. Russell Abbey, at the corner of Front and Princess Street, was the home to Peter Russell, his sister Elizabeth, and the slaves held within their household.

Peter Russell

Unknown, after a painting by George Theodore Berthon

1890 circa

Watercolour

Gift of J. Ross Robertson

Peter Russell was a member of the Executive Council of Upper Canada, and held the position of president and administrator of Upper Canada from 1796-1799, in the absence of Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe. Peter Russell lived in the Town of York with his half-sister, Elizabeth. Included in their household were Peggy, a slave, and her children Amy, Milly, Jupiter and one other child. Peggy's husband, Pompadour was a free Black employed by the Russells.

The Pompadour family courageously resisted their enslaved condition. On more than one occasion, Peter Russell sought to sell Peggy and her son, Jupiter, in order to punish her by separating her from her family. In 1808, Russell bequeathed his property, including Peggy and her children, to his sister, Elizabeth Russell.

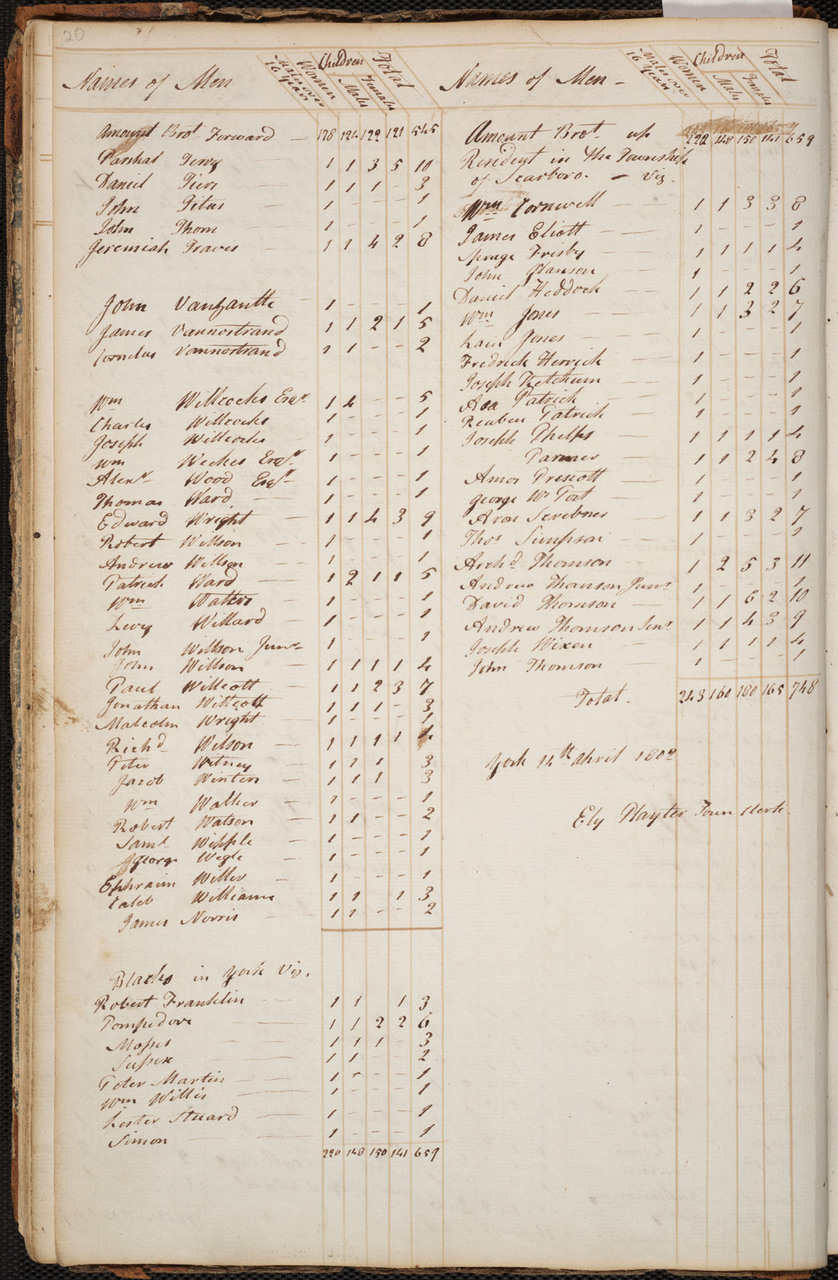

York, Upper Canada Minutes of town meetings and lists of inhabitants, July 17, 1797-January 6, 1823

York, Upper Canada, 1797-1823

By 1802, black residents were listed separately. Eighteen African Canadians were listed, including six children. One was Robert Franklin, a free black man who came to York with Peter Russell as a senior servant. Franklin had hoped to take up one of the free land grants offered along Yonge Street. The government denied him such a valuable a lot, and he eventually settled on a farm in York Township.

Letter from Henry Lewis to his master, William Jarvis

Niagara-on-the-Lake, Schenectady, New York, May 3, 1798

William Jarvis fonds

Following his escape to Schenectady, New York, Henry Lewis wrote to his former owner, William Jarvis, Provincial Secretary of Upper Canada, asking to be allowed to purchase his own freedom. In his letter, Lewis wisely defers to Jarvis, stating that although he was well treated in the Jarvis household, his reason for leaving was of a “personal nature”, most likely related to the behavior of Hannah Jarvis. But most significantly the letter includes a memorial to the importance of freedom, and outlines a plan to repay his former owner for his purchase price. Having little choice, Jarvis agreed to the sale.